Celebrating 50 Years of the Harley-Davidson XR750: Part II of IV

It’s a definitional reality of racing that you can’t win by sitting in place. For the legendary Harley-Davidson XR750, that was every bit as true in the race shops as it was on the race tracks.

The basic platform has remained recognizable as the genuine article throughout its existence; the iconic XR750 name is not merely a common designation shared by an endless string of complete technical overhauls and reinventions as one might find in MotoGP.

That said, winning an average of ten-plus races per season over the span of a half-century required non-stop evolutionary innovations in order to extract every last molecule of performance from that basic platform.

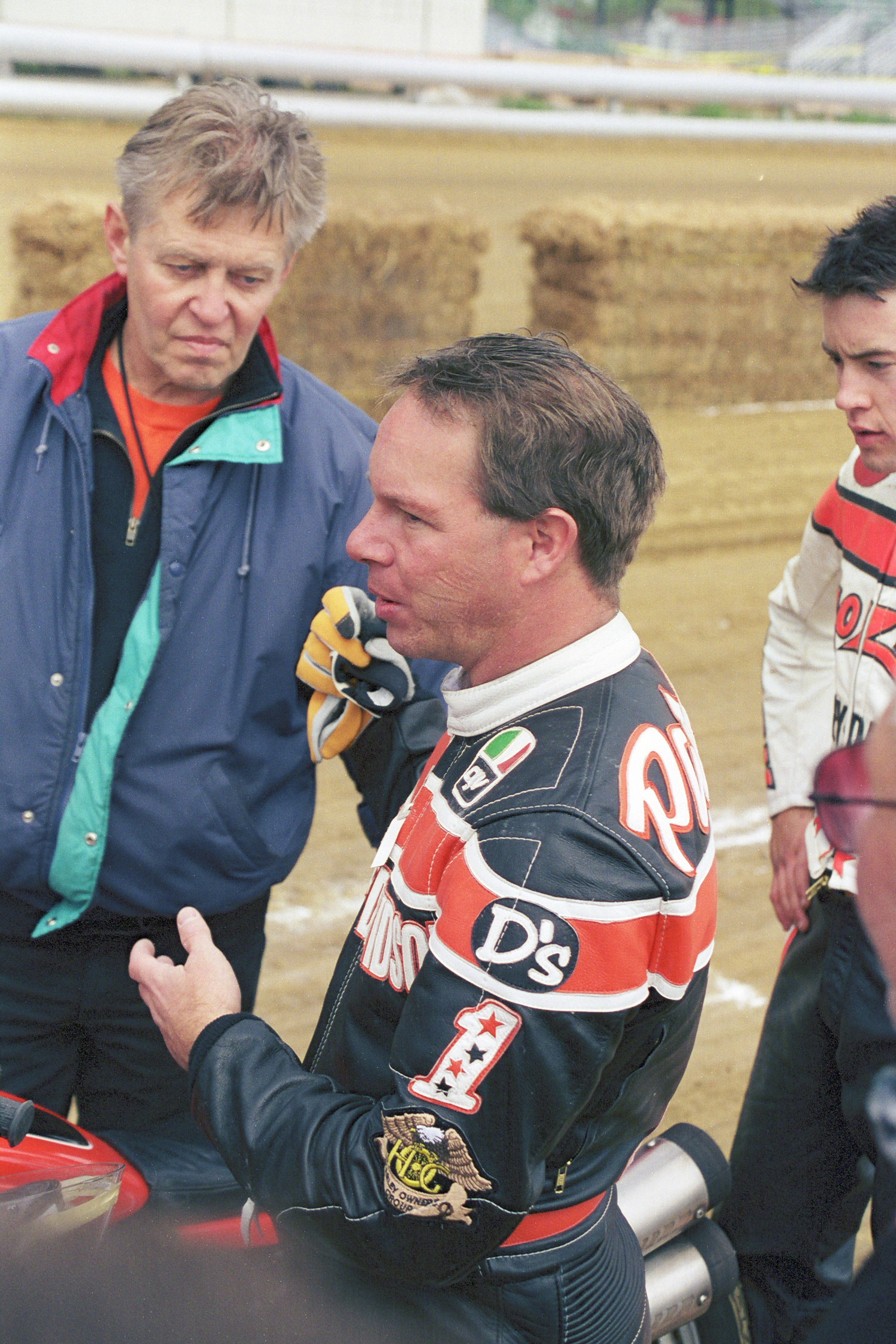

Nine-time Grand National Champion Scott Parker said, “Think about it: The thing was designed 50 years ago and was competitive up until... I think people are still riding them from time to time today. They could still win races, that's the cool thing about it.

Parker exhibiting the XR750's unbeatable speed.

Photo: Dave Hoenig, Flat Track Fotos

“Here you've got a motorcycle that is 50 years old and even through all the stages that it’s gone through to get here, there are some parts that have been there the whole 50 years, which is amazing.

“They kept trying to improve it and improve it and improve it, but it still had the same basic design… They just kept innovating, getting a tad bit better constantly, and here it is, still competitive all these years later.”

Ironically, the most successful racebike of all time is one Harley-Davidson likely would have preferred not to have to build, only designing it when its hand was forced.

Afterall, H-D already had its generational flat track machine in the flathead KR750 -- at least up until it didn’t. Introduced a year before the Grand National Championship was first organized as a series in 1954, the KR750 immediately proved the GNC’s dominant mount and didn’t relinquish the throne for years.

The KR stormed to 13 of 16 Grand National Championship titles from ‘54-’69 while racking up a mammoth tally of race wins along the way, including every single one available in 1956.

But the rulebook was updated in 1969, eliminating the 250cc displacement advantage for sidevalve machines that the KR750 had previously enjoyed. As a result, the gates were kicked down by Harley-Davidson’s more modern overhead valve-armed British rivals and the writing was on the wall.

Gene Romero won the GNC on a Triumph in 1970 followed by Dick Mann aboard a BSA in 1971.

Under factory race manager Dick O’Brien’s watch, Harley-Davidson moved quickly to adapt to the new regulations, Frankensteining the original “Iron XR750” from parts taken from the 883cc Sportster XLR outlaw racebike. In order to meet the 750cc displacement limit, the stroke was decreased while its bore was increased, but the pushrod V-Twin retained the XLR’s cast-iron head and cylinders.

13-time Grand National Championship-winning tuner Bill Werner was already employed in Harley-Davidson’s race shop at the time, kick-starting his long association with the XR750 from its nascent beginnings.

“I don't think there's anyone who's been around an XR750 more than Bill,” Parker said. “He was there from the very beginning and eat, slept, and drank that bike. He loved them.”

Bill Werner in consult with his rider Scott Parker at the 1999 Du Quoin Mile.

Photo: Dave Hoenig, Flat Track Fotos

Werner said, “Yeah, I was privileged to be there at its inception and through all its development to its peak era. I was there right for the transition from the flatheads to the XRs, from the cast-iron XRs through the Aluminum XR -- engine development, frame development, and all that sort of stuff. Not only was it a thrill, but it's something you can look back at and say it's part of your legacy.”

Reflecting on the initial task of bringing the original Iron XR to life for the 1970 season, Werner admitted, “It was a huge process. We had failures converting an 883 Sportster into a 750. We had to destroke it and we had flywheel issues. And then after we got those solved, we had to deal with the things overheating because they made good horsepower but they'd get too hot. We had all kinds of challenges to cooling them off.

“I had the sole task of converting them to dual carburetor kits. I welded up all the heads on the factory conversions, taking a front head and making two front heads and a dual-carb conversion out of it. I had to plug an exhaust port and move it from one side to the other to make the rear head.

“And I spent the better part of a year welding up all the heads, brazing them all up, and sticking them in 55 gallon drums of powdered asbestos to cool for two days because they'd crack through the valve guides if you didn't do that.”

Harley-Davidson fielded the Iron XR750s for just two seasons while an alloy-based rethink was being readied. While not remembered nearly as fondly as the more refined XR750 to come due to performance and reliability issues, history has given it something of a bum rap.

Mert Lawwill debuted the Iron XR in winning fashion in a non-sanctioned outlaw race at Ascot, and then scored its first official GNC race victory weeks later, still early in the ‘70 season, at the Cumberland Half-Mile. It went on to rack up a combined ten victories during the 1970-1971 Grand National Championship seasons, providing clear evidence that Harley’s KR successor was destined to become a force in its own right from the start.

Werner said, “The cast-iron XR actually won races in its first year. We had failures and it didn’t win the championship, but it won races.

“We ultimately knew it was a stop-gap effort, and we were going to transition to the Aluminum XR. I got in on the ground floor of that too and was part of the dyno testing.”

The transition was more than just a simple elemental matter as the nickname change suggests. Harley-Davidson’s race department took full advantage of its second chance to introduce a new-generation racebike and leaned heavily on the lessons learned by the iron machine.

“Some of the things we learned in the flywheel area we incorporated into the '72 Aluminum XR, even though it had a different bore and stroke and all that,” Werner explained. “We changed the lubrication system from a timed breather system to a mini-sump system. We changed the cam shaft diameters because the ball bearings closest to the crankcase would fail; we converted them and put in needle bearings on the crankshaft side.

“Cam development was huge too because the engines were capable of more RPM -- they had a bigger bore and shorter stroke than the cast-iron XR. The first heads had ports about the size of your finger, and we had to do all the cylinder flow work... You're better off casting them with too much material because you can't put it in and you can always take it out.”

The intensive and radical (re)development paid immediate benefits. With Mark Brelsford at the controls, the Aluminum XR finished as race runner-up in its national debut at the Colorado Springs Mile, won in its second race at the Louisville Half-Mile, and earned the Grand National Championship in its very first attempt.

The rest was record-book obliterating history, as the Aluminum XR750 would go on to win 492 of the XR’s ridiculous 502 premier-class race wins, along with its insane tally of 37 GNCs.

Of course, in order to achieve those results, continual development was required the entire way.

When asked, Werner rattled off various updates, stream-of-consciousness style. “The ports evolved from round to oval over time. The rocker shafts got changed from a clamp-type arrangement that held the adjustment to a nut-type arrangement that tightened it up. The shaft diameters changed. The RPM went up. The spring rates went up. We changed from steel valves to titanium valves.

“The engines used to start at maybe 7800 to 8000 rpm max, and by the end of its transition we were turning at 9500 rpm. We went from quarter-speed oil pumps to half-speed oil pumps to circulate more oil over the engine to cool it better. We went from aluminum cylinders with cast-iron liners to all-aluminum cylinders to nickel-plated aluminum cylinders that were lighter and cooled better.”

Over the years, all of those small improvements added up (and up… and up).

Parker said, “The first XR I got on had like 70-odd horsepower. By the time I was done, it was somewhere around 105. Over just the time that I rode one, that's the difference we’re talking about.”

But not all of the development work was dedicated to a never-ending quest for more power, nor were they all so small and incremental. A full decade before Honda turned the Grand Prix world on its head with the introduction of the “big-bang” firing order for the NSR500 in 1992, H-D experimented with the same concept and for the same reason -- seeking both maximum traction and a more rider-friendly mount.

Werner said, “One of the things we did on the XR was what they called “twingling.” The standard XR fires a 157.5-202.5 degrees... It's a 45-degree V-Twin -- one cylinder fires when the other one is on the exhaust stroke. It's not symmetrical -- it can't be because it's a 45, single crank.

“I thought, what if I fired them 45 degrees apart, just 45? All you have to do is turn two camshafts 180 degrees, turn one of the ignition shafts 180 degrees, and it will fire 45 degrees apart.

“It sounded like a big single. Some guys loved it, and some guys couldn't tell much difference. It depended on the type of rider you were. If you were a real brave, aggressive guy... not that big of a deal.

“While we were first testing them, I was with (three-time Grand National Champion) Jay Springsteen at a dragstrip in California. I ran the “Twingle” down the racetrack, and he asked how it felt. I told him it felt butt-slow. He said, 'Well, let's compare it to the other bike.' So we drag-raced them side-by-side and they were dead equal. We switched bikes and they were still dead equal.

“When you got on the Twingle, the sensation of speed was lessened. You didn’t hear that rush of high RPM. It's like the difference between riding a single and a twin. So timid riders loved the Twingles because they could go faster than their normal intestinal fortitude would have let them.”

Whether it was actually down to rider temperament or something more tangibly mechanical, the Twingles proved to be serious weapons on more slippery surfaces and remained a popular choice of top riders until they were ultimately prohibited from competition in 2006.

Next time: The XR750 meets its match.

Photo: Harley-Davidson

Latest news

Through the Briar Patch